What is a Data Protection Officer? (DPO)

For many organisations operating within the European Union, the concept of the data protection officer will be familiar. It is enshrined in Articles 37-39 of the GDPR, which set out the test for when a DPO is required, as well as requirements in relation to the position of the DPO and the tasks they must undertake. Guidance on these requirements was produced by the Article 29 Working Party in the run up to GDPR and later endorsed by the European Data Protection Board.

Under the GDPR, organisations must choose a DPO based on their professional qualities, expert knowledge and ability to fulfil their tasks, which include advising the organisation on their data protection obligations, monitoring compliance, advising on data protection impact assessments, and liaising with the regulator. In practice, the role can be fulfilled by individuals with a range of technical and professional backgrounds and the position (and any team around it) can be structured in a variety of ways, depending on the organisation.

The concept of the DPO is not unique to the EU, and global organisations should be aware of requirements in other jurisdictions, to understand the extent to which obligations overlap, whether the same individuals may be appointed to act as DPOs across multiple jurisdictions, and how to operationalise the role appropriately. The purpose of this article is to delve into requirements across the Asia-Pacific region (APAC).

As more jurisdictions in APAC have adopted (and enhanced) comprehensive data protection laws, requirements to appoint DPOs have become more widespread. One recent example is Malaysia, where amendments to the Personal Data Protection Act require mandatory appointment of a DPO from 1 June 2025. In some cases, requirements closely mirror those under GDPR, but there is significant variation, even when it comes to the terminology used. In China, for example, the term “personal information protection officer-in-charge” is used, while in Australia, New Zealand, and South Korea, it is privacy officer or chief privacy officer. In India, there is a role known as “Grievance Officer”, although this is a narrower concept than in other jurisdictions. For ease of reference, in this article we will generally use the term DPO.

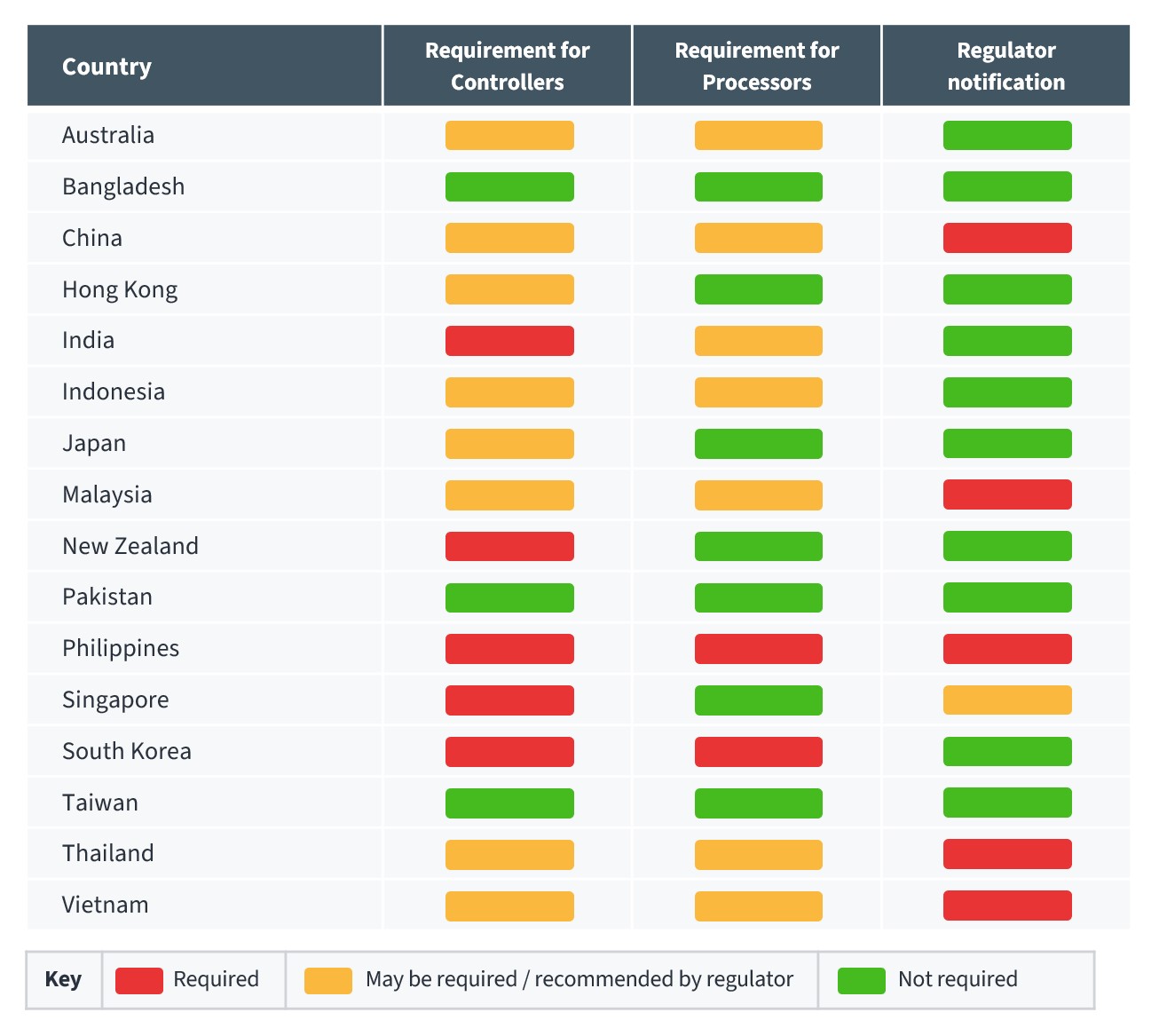

Do I need to appoint a DPO?

To begin with, we will provide an overview of where DPOs are required in APAC. In some cases, appointment of a DPO is mandatory wherever personal data is processed, while in others a DPO is required where certain criteria are met (as with GDPR). There are also certain jurisdictions where appointment of a DPO is not legally required but is recommended by the regulator. The below table provides a comparison of requirements across APAC, including obligations to notify the regulator about the DPO’s appointment.

Mandatory in all circumstances

- For some jurisdictions, there is a general requirement to appoint a DPO, with no minimum threshold for the obligation to apply (see for example New Zealand, Singapore, and South Korea). In the Philippines, as well a blanket obligation to appoint a DPO, organisations with multiple branches or sub-offices may also choose to appoint a “compliance officer for privacy” in each of these

- In India, organisations are required to designate a Grievance Officer (to deal with complaints in relation to personal information) and publish their name and contact details on the organisation's website. As mentioned above, this role is more limited than the traditional concept of a DPO. However, it is important to note that new requirements will come in once India’s new Digital Personal Data Protection Act is implemented

Required subject to certain criteria

- In China, under the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL), controllers must appoint a DPO if the quantity of personal data that they process reaches the threshold set by the national cyberspace authorities. Although these thresholds have not yet been set, under the PI Security Specification (a recommended national standard) a DPO (or department) should be appointed for organisations (i) with at least 200 staff and a primary business involving handling of personal data; (ii) that process personal data of more than a million data subjects (or expect to do so within 12 months); or (iii) that process sensitive personal information of at least 100,000 individuals

- Certain jurisdictions closely mirror GDPR requirements for appointment of a DPO. In Indonesia, for example, organisations must appoint a DPO if their core activities require the organised, systematic monitoring of a large volume of personal data or of a large volume of sensitive personal data or data relating to criminal activities. The test is similar in Thailand, although simply processing sensitive personal data as a core activity is enough to trigger the requirement (there is no need for this to be a high volume)

- In Malaysia, from 1 June 2025, organisations need to appoint a DPO if their processing of personal data involves: (i) personal data exceeding 20,000 individuals; (ii) sensitive personal data including financial information exceeding 10,000 individuals; or (iii) activities that require regular and systematic monitoring of personal data

- In Vietnam, organisations that collect and process sensitive data are required to appoint a DPO. However, our local counsel’s view is that it is best practice for all organisations that process any kind of personal data to appoint a DPO

Recommended by the regulator

- In Japan and Hong Kong, while there is no statutory requirement to appoint a DPO, the regulators in these jurisdictions recommend appointing, and many companies do appoint, a DPO or person responsible for the handling of personal information (as part of a sound privacy management programme)

- Similarly, in Australia, appointment of a DPO is not required under the Privacy Act, but the regulator has issued guidance recommending that organisations appoint one as part of good governance mechanisms to ensure compliance with the Privacy Act. It’s also worth noting that appointment of a DPO would become mandatory under proposed reforms to the Privacy Act

Recommended by local counsel

- In Taiwan, there is no requirement under the current Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA) for an organisation to appoint a DPO. However, the PDPA provides that an organisation must have sufficient resources to comply with the PDPA and put in place sufficient security measures. Therefore, in our local counsel’s opinion, appointment of a DPO is best practice to demonstrate such resources are in place. Similarly to Australia, a requirement to appoint a DPO is included in draft amendments to the PDPA, which are under public consultation at the time of writing

Who can be a data protection officer?

Skills and experience

Many jurisdictions in APAC set out specific requirements or recommendations on the skills and experience required for DPOs. In some cases, these are quite generic – as with the recommendation in China to have professional knowledge of data protection and relevant management experience, or the requirement in Indonesia for DPOs to be appointed based on their professionalism, understanding of the law, practice as DPO and ability to fulfil their obligations. In New Zealand, the only requirement is that the individual chosen must be capable of fulfilling the statutory responsibilities of the role.

In Thailand, while specific requirements on who can be appointed are yet to be implemented, there are detailed recommendations on the skills and knowledge required, which (as well as multiple years’ data protection experience) include: expertise in IT and IT Security; a profound understanding of the organisation; personal qualities including integrity, initiative, management skill, discretion, ability to assert oneself in difficult circumstances; motivation to be a DPO; and interpersonal skills, including communication and negotiation skills, conflict resolution skills, and ability to build working relationships. It is also worth noting in Thailand that the DPO may perform other duties, but the organisation must give assurance to the regulator that these are not contradictory to or inconsistent with Thailand’s data protection law.

South Korea is an interesting example, where recent amendments to the law set additional requirements for organisations with annual sales or income of KRW 150 billion or more, and which process the personal data of more than 1 million people or the sensitive and uniquely identifiable information of more than 50,000 people. Such organisations must appoint DPOs with at least 4 years combined experience across data protection, information security, and IT (including a minimum of 2 years of data protection experience). These requirements must be met by 14 September 2026.

In Singapore, while the law does not require a DPO to be certified or trained, this is strongly encouraged by the regulator, which has co-issued a certification for this purpose.

Some jurisdictions propose a split in roles, potentially with different skills required for each. In Australia, the regulator recommends appointing a senior member of staff to have overall accountability for privacy, as well as a key privacy officer who understands the organisation’s responsibilities under the Privacy Act. In the Philippines, organisations may have “compliance officers for privacy” for different parts of the corporate group, whose skills and experience should be proportionate to their function.

Organisations should review these requirements and consider what is required of the role by reference to the specifics of the organisation, while remaining mindful of potential local differences.

Position within the organisation

In terms of the DPO’s position within the organisation, the regulator recommends in Hong Kong that in larger organisations the DPO should be a senior executive member. In South Korea, the DPO must be either the owner or representative of the organisation or an executive director of the organisation (and if the organisation has no executive directors, the head of a department in charge of affairs relating to personal data processing may be appointed as the DPO).

In Malaysia, the requirement is that the DPO has access to senior management (which is similar in Thailand, with a direct reporting line to senior management recommended).

The guidance in Singapore offers alternatives, by suggesting the DPO should either be a member of the organisation’s senior management team or have a direct reporting line to senior management.

Internal or external

Most jurisdictions are silent on whether the DPO should be internal or external to the organisation, or else the rules offer flexibility. For example, the law in Malaysia states explicitly that the DPO may be full or part time and/or appointed via outsourcing services.

In Thailand, to avoid conflict of interest between the duties of the individual as a DPO and his/her other duties, it is recommended that the DPO should not also be a controller of data processing activities. It’s also recommended that the DPO not be an employee on a short-term employment contract.

In the Philippines, the regulator recommends the DPO be an employee (ideally regular/permanent – with a contract of at least two years to ensure stability), rather than a consultant.

Group companies

In general, appointing an individual to act as the DPO for multiple organisations across a corporate group is likely to be acceptable across most of APAC.

In Singapore, the law requires organisations to assess what a reasonable person would consider appropriate in the circumstances in deciding whether a single DPO is sufficient for the entire group of companies or if a team of DPOs should be appointed. Appointing a single DPO for multiple entities is also expressly permitted in Thailand, provided the DPO is conveniently contactable from each business office of the organisation.

In the Philippines, a single DPO may be acceptable for a group of related companies, subject to the approval of the regulator, but each of the other entities in the group must still have a compliance officer for privacy.

However, in South Korea a single DPO will generally not be sufficient for a group of companies, as the DPO must be the owner, the representative, an executive director or department head of the appointing organisation.

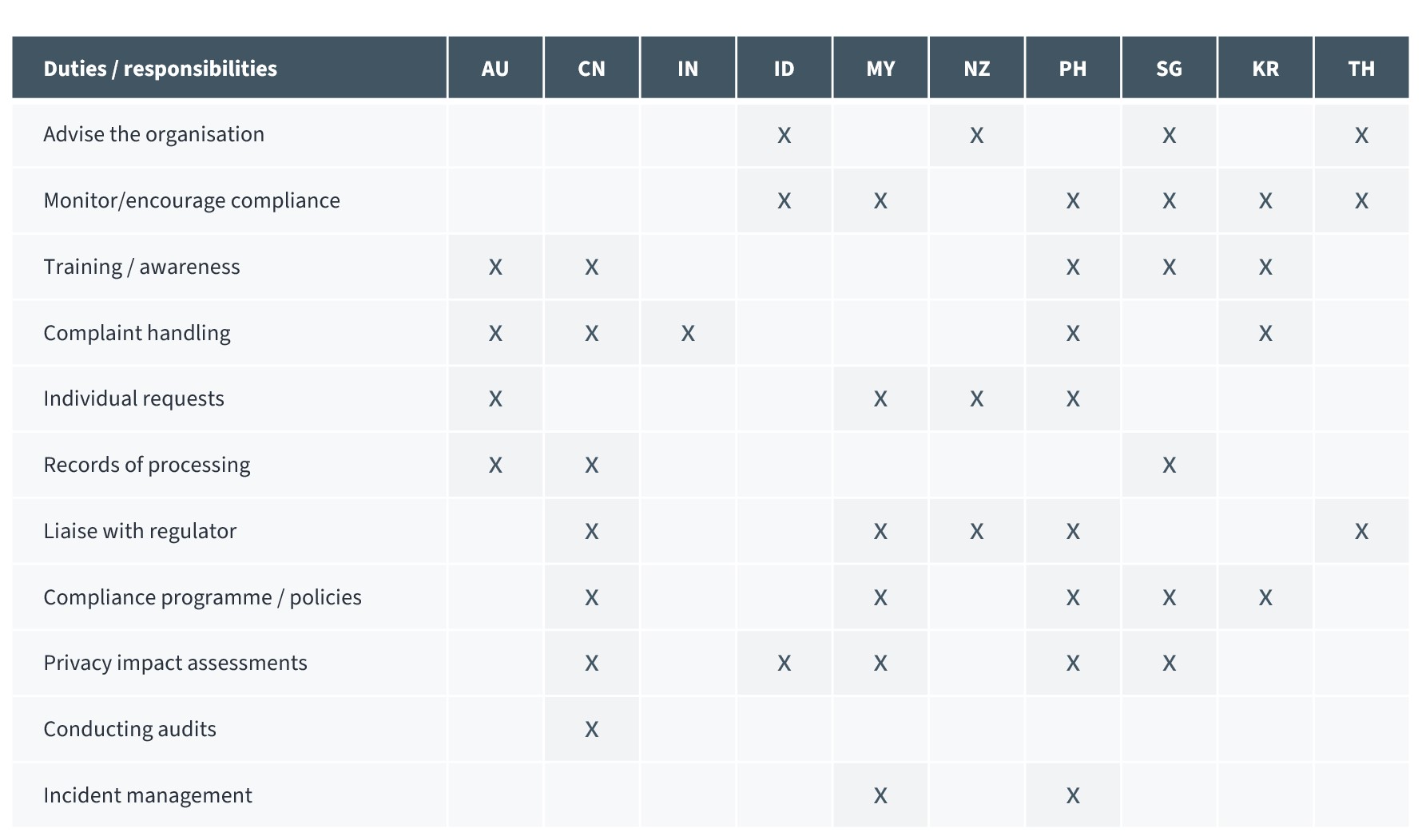

DPO duties and responsibilities

In terms of duties and responsibilities, there is significant overlap between jurisdictions in APAC on what the rules require or guidance suggests. One obvious outlier is India, where the responsibilities of the Grievance Officer are limited to complaint handling.

The table below provides a summary of the key obligations across a number of key jurisdictions. It is important to note that this table represents the points that are stated explicitly in the law or regulatory guidance, but in many cases the duty will be implicit (for example the DPO will generally advise the organisation in relation to data protection matters in practice, even if this obligation isn’t explicit).

When considering appointment of DPOs across APAC, there are clearly opportunities here for synergies, for example where a DPO may be able to integrate training programmes or assessment processes across multiple jurisdictions. Nevertheless, the DPO will still need to be sensitive to local variations in the rules when building out these processes and will need to be sufficiently well-versed in the laws and languages of the relevant jurisdictions to effectively discharge their duties (particularly in relation to such areas as handling individual requests and complaints and liaising with regulators).

Looking for expert insights on international privacy laws?

Request your free Rulefinder Data Privacy trial today